Preview The Orchid Show: Mr. Flower Fantastic's Concrete Jungle

Get a sneak peek of the New York Botanical Garden's exquisite new exhibition!

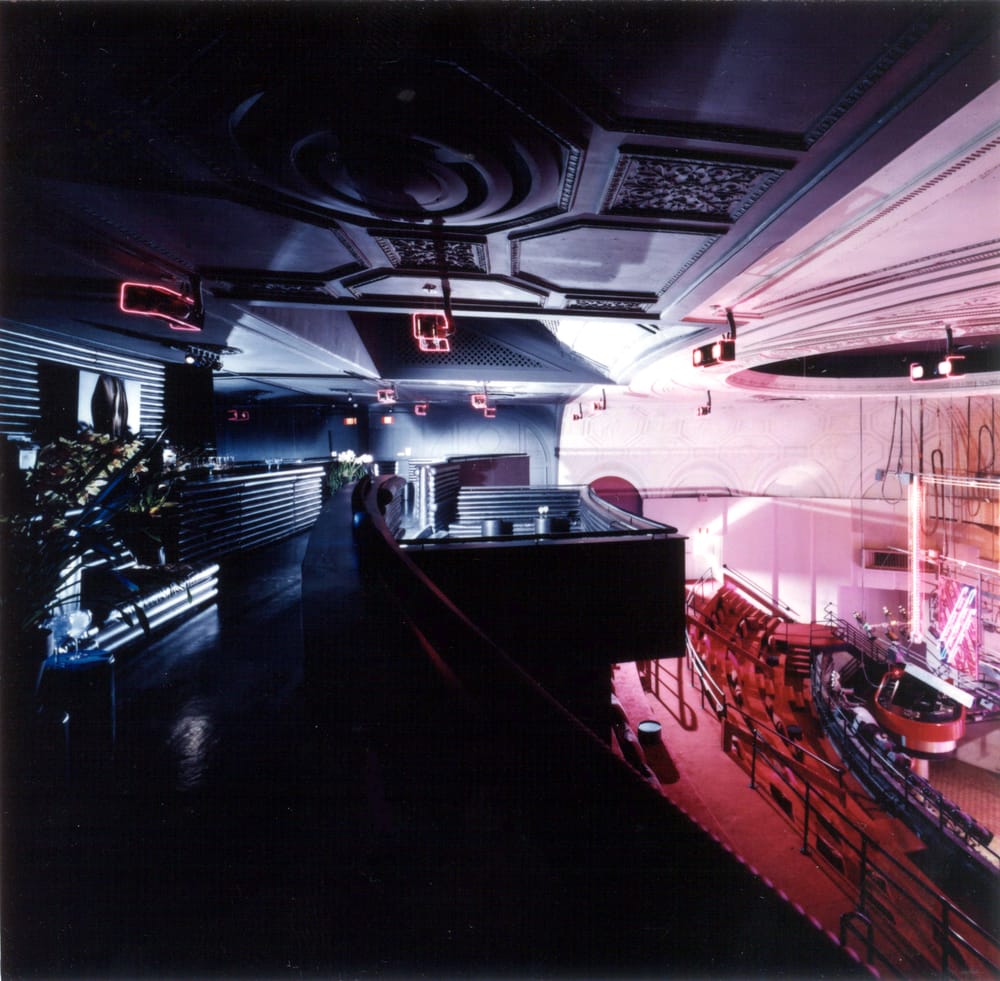

As the iconic NYC venue "reopens" for a special event, we chat with the nightclub's original architect about his most notable designs!

Renowned architect Scott Bromley is best known for designing the era-defining nightclub Studio 54 (now home to the Roundabout Theatre Company), but that's not the only mark he left on New York City. During his career, Bromley spent time at the family firm of Emery Roth & Sons, often collaborating with Richard Roth, Jr. As Studio 54 prepares to "reopen" on September 10th for a Valentino Beauty event, Roth's biographer Jo Holmes sits down with Bromley to discuss his approach to the club's design and his creative partnership with Richard.

254 West 54th Street as preparations for the reopening took place on September 9th

Bromley was born in Canada in 1939 and moved to New York in 1964 after graduating from the School of Architecture at McGill. He grew up preferring to draw, design, and fix things over academic study. He did two stints at Emery Roth & Sons and worked for one of the original ‘starchitects,’ Philip Johnson, before starting his own firm in 1974. Bromley has become the go-to architect for beach house design and renovation—especially on Fire Island, where he has lived for many years.

Holmes: How did you end up working at Emery Roth & Sons?

Bromley: I was young and I wanted to be in New York—after all, it’s the unacknowledged capital of the world! I arrived in January 1964 and noticed an Employment Agency near Grand Central. I went in and showed someone my shoebox full of drawings. Within a few hours, I had an appointment at Emery Roth & Sons. I showed the drawings to Irving Gershon, the Head of Design, and he offered me a job there and then. I guess I was earning around $90 a week then.

By the time I was 26, I’d designed 26 skyscrapers. I worked there until Philip Johnson and I met. He was pursuing me to come and work for him. So, I went to Richard in 1966 and said, “Richard…if Philip Johnson asked you to work for him, would you?” And he said, “I certainly would.” So, I said, “Well, he did…and I am!”

Richard said fine, he said good luck. I mean, I think he was sorry to see me go, but realised I had a little bit of talent and would benefit from going to work for Johnson. But for the next three years, all I got were invitations to come back to them and be Head of Design!

With Philip Johnson, I designed an addition to the Boston Public Library and some significant buildings in Texas, among others. Three years later, in 1969, all of a sudden, John Burgee was going to be Philip Johnson's partner. And I thought, well, it isn't ‘Johnson-Bromley,’ it's ‘Johnson-Burgee!' So, I decided to take up Emery Roth & Sons’ offer to go back. That's when Richard and I really worked hand in hand together.

And you worked on some of the buildings we’re covering in our series?

Yes. I worked with Richard on Tower East. I’d say I was a good planner and insisted every bedroom should have a bathroom—and every multi-bedroom-and-bathroom apartment also had to have a powder room. That was a big change for the late 20th century.

I worked on both 345 and 450 Park Avenue. I call 345 the ‘Chiclet building’ because it looks like a lot of Chiclets! 450 was the last building I worked on before I left. It has arch windows and a public space on the side.

Like Richard, I got along well with Mel Kaufman—working on 77 Water Street, among other buildings—and with Harry and Leona Helmsley. My first encounter with Leona was…interesting. During my original stint with Emery Roth & Sons, Richard Sr. sent me to meet her. She was living in the Park Lane Hotel— we’d designed the façade —and she wanted a swimming pool built in the penthouse. I was maybe 28 years old. It was 11 o'clock in the morning, and I was ushered in. Then she entered—wearing nothing but a bathrobe and mules!

Of course, I knew other clients, like the Rudins, who built a lot of apartment buildings, and the Uris family, who often worked with Emery Roth & Sons, including commissioning 55 Water Street.

What was the key to your relationship with Richard?

We just clicked. We had an aesthetic in common: we liked simplicity and straightforwardness—and no fluff! And we had a great time. He would include me in family stuff…and I was this gay kid from Canada, six foot three with gray hair. You know, being gay in the 1960s and 1970s was not the easiest thing, but it was never brought up. Richard was very easy-going. There was a job in Lisbon where things got a little tricky because the client’s son was hitting on me. Richard’s wife, Alene, would roll her eyes about that!

Like Richard, I’m dyslexic—in fact, I didn’t read a book until I was 40! Maybe that meant we communicated in a particular way, like ‘soul brothers.’ We would sit beside each other, drawing and talking about what might or might not work—we were a team. And, as I said, I felt like I was adopted by the family.

Later in life, when Richard moved to Freeport and then back to Florida, he would send me emails and invite me to visit. And Alene and I would chat—you know, our relationship didn’t end when Richard retired.

What made you leave Emery Roth & Sons a second time?

In 1974, there was a mini crash, and Richard said, “Listen, we don’t really have any work.” So, I took the summer off and spent it on Fire Island. When I returned in September, he said there still wasn’t any work. I told Richard he had to fire me so I could collect unemployment insurance. And he did, so then for a while I was making $90 a week again, ten years on!

Then I started my own business. I worked out of my apartment for a while. I’d done lots of lobbies and interior stuff with Emery Roth & Sons, so I had a good sense of interior design. The mini crash meant lots of people didn't have money to build, but they were renovating. So, I kind of billed myself as an interior architect. And then we did lots of conversions and so on. You know, it's hard for me to separate exterior and interior design. Architecture isn’t just the exterior—it’s the whole environment.

And your firm did projects for Emery Roth & Sons over the years?

Yes, for various buildings they were doing, they asked us to design the lobby and the common spaces. We were trying to be really innovative and have like a waterfall or a pool, say. Richard was always interested, asking, “How do you come up with this stuff?” and was always very complimentary. So, yes, we did interiors and planning for Richard. One project I remember well was 805 3rd Avenue with columns that shot through a glass façade.

I recall Jerry Caldari, my business partner, and me in my office working over Thanksgiving Day weekend to get something done for Richard. If Richard wanted it done, it had to be done! We were such good pals, and he relied on me and that was a compliment to me.

Having designed many tall buildings in your career, what do you make of the super-skinny super-tall buildings in Manhattan?

They’re scary to me because I don’t like heights—and they sway six or seven inches in the breeze! I can't imagine that they make economic sense, but if the demand for living up in the clouds is there, it’s fine. It's not for me. And I don't think they're pretty at all. I like good design, but when it gets extreme, it doesn't make sense to me visually, and it doesn't make sense to me architecturally. I mean, of course, I don’t disapprove of tall buildings. I liked the World Trade Center—it was gutsy, and I liked the idea of ‘twin’ buildings.

You famously designed the iconic nightclub Studio 54. How did that come about?

In 1977, I designed a store called Abitare. It was a two-story building, but it was very sculptural, with 14-foot panes of glass clipped onto a frame. There were no mullions. It was the first time that had been done in Manhattan, and it won awards. Then there was a Times article about young architects, including me, and I got a call from a gal called Carmen D’Alessio. She said, “Listen, I have a couple of boys who have this discotheque in Queens, but they want to do something in Manhattan, and we’ve found this old TV studio on 54th St. that used to be an opera house.” So, she asked if we could meet there. The ‘boys’ were Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell.

At the time, Ron Dowd (another architect) and myself, Renny Reynolds and Brian Thompson, had this little office on two floors that was only 16 feet by 16 feet. Brian was a wonderful lighting designer, and Renny was doing flowers and had a flower shop. We all ended up involved in Studio 54.

Ron and I went along, and as you’d expect in an opera house, there was a raked floor and a raised stage. And I said—I was always so bold about what I wanted to say—“You know, everybody wants to be a star. Where are the stars? They’re on the stage. So, let's make the stage the dance floor.” And we used unheard-of materials —we had astroturf for the floor, which is usually, you know, on a football field!

The boys were smart about it. They closed in August because everybody leaves Manhattan, and then we’d renovate the club. We made it different every September. We designed the famous moving bridge. Of course, there are wonderful stories…you know, sex, drugs, and rock'n'roll!

Studio 54, Photo by Jaime Ardiles-Arce Photography, Courtesy of Bromley Caldari Architects

It was open for about three years. It closed when the boys went to jail for tax evasion. Years later, in October 2011, radio station Sirius XM reopened the club for ‘one night only.’ I worked with Karin Bacon, Kevin Bacon’s sister, on the design. We got the famous ‘spoon in the moon’ back, we rebuilt a couple of banquettes that Ron Dowd and I had designed, and we got some original lighting back. It was a huge success. In fact, somebody offered Scott Greenstein, President of Sirius XM, a million dollars to keep it open another night!

You’re 86 now…and still putting in a day’s work every day?

Yes, I have a meeting tomorrow with clients whose beach house we’re renovating. I love what I do! I love designing. I've always got a pencil or pen in my hand. I'm always sketching. Design is my life, and I love to be able to share it. When clients say, “This is much more than I dreamed of,” you know, that makes you glow a little and think ‘OK, I can keep going.’

There’s no building per se that stands out—it’s the lifestyle architecture can bring, and the people I’ve met, I’ve appreciated. I think that’s what Richard felt, too. He was very popular, he was very well liked as a personality—you know, he was lots of fun. It was a joy just to sit beside him and sketch.

Subscribe to our newsletter