You Can't Eat the Food at this MoMA Mart Pop Up in NYC

Nothing in this pop-up store is what it appears to be!

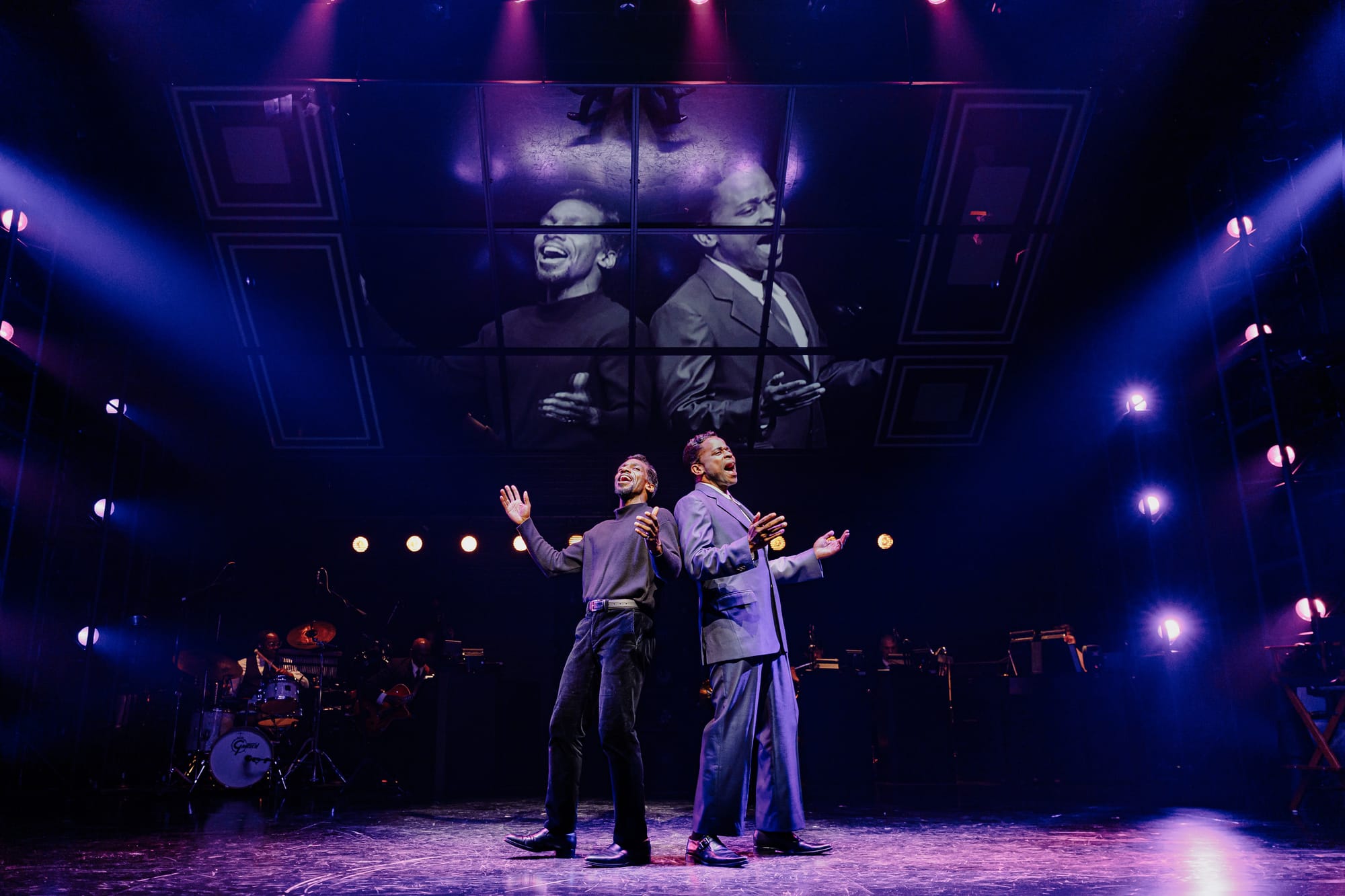

The new bio-musical about Nat "King" Cole by Colman Domingo and Patricia McGregor at the New York Theatre Workshop stars Dulé Hill and Daniel J. Watts.

Lights Out, presented by the New York Theatre Workshop, has all the makings of a dazzling success: phenomenal performers, legendary music beautifully delivered, an enchanting set, and a compelling story about the tremendous wrongs done to a celebrated man, Nat "King" Cole.

At the time of his death at age 45 in 1965, Nat 'King' Cole had sold more records than anyone else in history, with the sole exception of Bing Crosby. As Down for the Count points out, this was an amazing achievement given that Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles, Buddy Holly, and Ella Fitzgerald were performing at the same time and at the peak of their powers.

Cole was so successful commercially that Capitol Records’ headquarters became known as “The house that Nat built.” He was an international star who toured the world, commanding the highest fees. He recorded songs in four languages: Spanish, French, Italian, and Japanese. And he is considered by many music critics to have been the finest jazz pianist of all time.

In 1956, Cole became the first African American to host a national television variety show, then the most popular form of broadcast entertainment. But the racism of the day meant that The Nat King Cole Show never secured a national advertiser to pay for what was an expensively produced program that regularly featured the biggest, best-paid stars of the day (although many, out of friendship with Cole, donated their time or worked for scale). By summer's end, the show was the number one variety show in New York City, wrote Will Friedwald in his biography of Cole, Straighten Up and Fly Right: The Life and Music of Nat King Cole.

Yet at Nat Cole’s urging, NBC reluctantly cancelled the show, which had lasted only 64 episodes. The show's closing was not only a loss for the network and Nat Cole, but also for New York, where the first episodes had been filmed. Like other major programs, I Love Lucy and George Burns & Gracie Allen, the Nat "King" Cole show eventually moved to Los Angeles in an attempt to keep costs down.

Video Courtesy of New York Theatre Workshop

Lights Out is about the show’s final taping on December 17, 1957. But it’s also about Nat Cole himself, and what he endured despite—or perhaps because of—being the first black superstar. When he called himself the "Jackie Robinson of television," he was almost surely pondering the horrific racism endured by the black superstar then playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Written by Colman Domingo and Patricia McGregor, the play opens in Nat Cole's dressing room before the taping of the final show. A somber Dulé Hill as Nat Cole is getting ready to go on the air while brooding over the network's inability to find a national sponsor for his show. The audience immediately understands that this won't be a joyful bio-musical like the uptown Just in Time, where an exuberant Jonathan Groff plays Bobby Darin. This is something altogether different.

With a flash of light and near-sonic boom, Daniel J. Watts as Sammy Davis Jr. leaps onto the stage. "I'm gonna warm you up," he tells the audience. Watts is an extraordinary singer and dancer. So far, so good.

But then we get the bad news: "Welcome to the fever dream," says Watts. Unsettling and bizarre, the fever dream that follows offers some 80 minutes of confusion. At no point are we sure of what is fact and what is a dream. Did Cole's good friend Peggy Lee promise to perform in that final episode and then not show up, betraying him profoundly? We know that Lee had previously appeared on the show ("My Heart Stood Still"), so what is factually correct here? And was Cole's producer (played by Christopher Ryan Grant) a despicable racist who warned him not to "monkey this up" for all the people who had worked hard to get him on NBC? The real-life producer was Bob Henry, a renowned director and producer who succeeded in expanding the Cole show from 15 minutes to half an hour. (Henry went on to produce the second national show hosted by an African American, NBC's revolutionary and immensely successful Flip Wilson Show from 1970 to 1974.)

Did the stage manager (Elliott Mattox) in those days use a yardstick followed by a sign reading “Appropriate Racial Distance” to ensure distance between Cole and white female guests? Very possibly, because it seems like a pretty far-out technique to make up, but we don't know for sure in this fever dream. Hill and Ruby Lewis, playing Betty Hutton, sing a spectacular “Anything You Can Do I Can Do Better” from “Annie Get Your Gun,” while Mattox wields his sign, disturbing the audience's enjoyment.

The show's peak, so fabulous that it eradicates all previous problems, is a ferocious tap duet or perhaps combat between Hill and Watts to "Me and My Shadow," conventionally sung as a ballad. In real life, Sammy Davis was a brilliant tap dancer, and Nat Cole was not, but this duet (tap choreography by Jared Grimes) summarizes what the play is trying to say.

For much of Lights Out, Watts has been playing an aggressively obnoxious id or dybbuk to Hill's publicly serene Nat Cole. Now, both sides of Cole's personality confront one another. Little is resolved, although those who remember the lyrics may be thinking: "Me and my shadow, Are always the same, Always in the game, We'll never quit." But of course, Nat Cole was forced to quit. And he placed the blame squarely on the advertising industry that catered to racism.

Video Courtesy of New York Theatre Workshop

Nat Cole's famous explanation for the death of his show was that New York's Madison Avenue was afraid of the dark. The racism of the day pervaded American life, and advertisers of the day feared racist boycotts. In Lights Out, Cole says, "We are not out there in the streets, raising banners, risking our lives just for the right to breathe. With this show that we've poured our blood, sweat, and tears into, THIS is our front line. In this little half hour, we have been able to gracefully inhabit an act of quiet revolution. There's no time for easy anymore."

But his quiet revolution made many black activists his enemies even as it incited the country's worst racial instincts. A few months before his NBC show debuted, he agreed to perform in front of a segregated white audience in Birmingham, Alabama. On April 10, 1956, in front of an audience of some 3,000 white people, he was assaulted onstage by members of the White Citizens Council who intended to kidnap and murder him. The violence made national news, and Frank Sinatra sent a jet to fly him from Alabama to Chicago, where activists criticized him harshly for appearing in front of segregated audiences. He responded that he was just an entertainer: "The Supreme Court is having a hard time integrating schools, so what chance do I have to integrate audiences?"

Thurgood Marshall, then chief counsel of the NAACP but soon to be appointed to the Supreme Court, said, "All Cole needs to complete his role as an Uncle Tom is a banjo." (Recounted in Daniel Mark Epstein's 1999 biography of Cole.) The cruelty and injustice must have hurt Cole profoundly. He had withstood so much. When, as a young superstar, he had tried to hold his wedding at the Waldorf-Astoria, where he had stayed, he was turned down because he was black. (Instead, he was married by NYS Congressman Adam Clayton Powell at Harlem's Abyssinian Baptist Church.) When he moved to a posh neighborhood in LA, Hancock Park, a cross was burnt on his front lawn, his dog was poisoned, and a bullet was shot through his window. And now he was being called an Uncle Tom by the counsel to the NAACP, for which he had given many benefit performances.

When the lights went out the night I attended, the audience sat in silence for a beat and then applauded wildly. We were rewarded with two breathtaking performances at curtain call: Hill singing a sublime, "The Party's Over," and Hill and Watts reprising their tap battle to "Me and My Shadow." There's an almost unbearable sadness and a fundamental longing in many Nat Cole songs that Hill captures beautifully. Is there also the rage suggested by Watts? Probably, but Cole's self-discipline was legendary, and we don't know. Which is why the playwrights opted for the fever dream technique that permits them to speculate.

What we do know, as PBS noted in a documentary last year, is that what we once thought of as Nat Cole playing jazz is what we now call America's classical music.

Lights Out: Nat King Cole

New York Theatre Workshop extended through June 29

Tickets: $59-$129

Written by Colman Domingo and Patricia McGregor, and directed by McGregor. Orchestrations and arrangements by John McDaniel, choreography by Edgar Godineaux, tap choreography by Jared Grimes, scenic design by Clint Ramos, costume design by Katie O'Neill, lighting design y Stacey Derosier, sound design by Alex Hawthorn & Drew Levy, video design by David Bengali, hair & makeup design by Nikiya Mathis. Samantha Shoffner is the Props supervisor and Norman Anthony Small is the Stage Manager. Vadim Feichtner is the Music Director. Casting is by Claire Yensen.

Subscribe to our newsletter