This op-ed was originally published on janos.nyc, by Janos Marton who writes our Today in NYC History column.

I think there is zero chance of developers walking away from this waterfront. Look at this view! This is the best view in New York City, maybe in the whole world. You’ve got the entire Manhattan skyline right in front of you.

– Councilmember David Yassky (Williamsburg/Greenpoint), 2005

In Williamsburg and Greenpoint, luxury condos have been popping up like mushrooms after the rain. Yet ten years after North Brooklyn was promised a 28-acre park on the East River, that park’s prospects seem as remote as ever, in danger of slipping away for good. Recently, neighborhood groups have revived the clamor for Bushwick Inlet Park. At stake is not only greenspace for a community that desperately needs it, but the fundamental legitimacy of the city’s land use policy. In 2005, Williamsburg/Greenpoint underwent an enormous rezoning, allowing today’s luxury buildings. That rezoning came with a promise from the city, and if the city cannot deliver Bushwick Inlet Park, New Yorkers should not trust the city when it comes to rezone their neighborhoods.

Some New Yorkers think of Williamsburg as a gentrified monolith, but it is full of working class communities that have been there for decades: Polish and Italian on the North Side, Puerto-Rican, Dominican and Hasidic on the South Side. These cultural groups have clashed a great deal over the years, but little has brought them together like waterfront development, long blocked off to all of them by heavy industry.

Activists began organizing around waterfront development in the mid 90s, collaborating on Brooklyn Community Board 1’s comprehensive 197-A Plan for the waterfront. A 197-A Plan is the most powerful (though still non-binding) tool under the City Charter for neighborhoods to chart their own long-term development, and this plan recommended large open spaces, public access to the waterfront, mixed use development along Kent Avenue, and a strong commitment to affordable housing. The plan was approved by the City Planning Commission in 2001 and City Council in 2002.

Yet in 2005, when Mayor Bloomberg went all in on his Olympic bid and needed the Williamsburg waterfront for beach volleyball, his administration tossed the 197-A plan in a recycling bin and put forward a whole new rezoning vision for the waterfront rooted in luxury development. The community fought that proposal with everything they had. Elected officials opposed it. People rallied at City Hall. Guerrilla activists in costume raised awareness. Articles were written. Forums were held. Multiethnic alliances were forged. TV on the Radio played a show in support of neighborhood activists! You couldn’t have asked for better democracy in action.

When modifications were made to the rezoning proposal, some remained upset, but others admitted that the affordable housing, public park and economic development opportunities made the deal a fair one. City Council Deputy Leader Brad Lander, then with the Pratt Center, raved, “The communities of Williamsburg and Greenpoint win because today there is a guarantee of new and permanently affordable housing, instead of a virtual guarantee that new development would price residents out of their homes.”

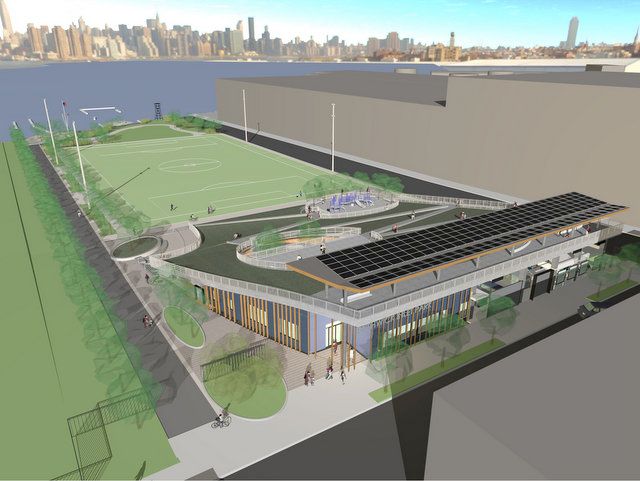

Rendering for part of Bushwick Inlet Park by Kiss + Cathcart

The revised 2005 rezoning, which featured 54 acres of new parkland, including a 28-acre park at the Bushwick Inlet, passed overwhelmingly. To help visualize the promised park, it would be 80% the size of McCarren Park, flank the Bushwick Inlet, and include a beach and boating. North Brooklyn is currently 5% parkland, a third of the city average, is nowhere near a major park, and has one of the lowest open space ratios in the city. If luxury condos were going to change the neighborhood forever, at least the neighborhood would be getting something it needed in return.

The 2005 deal wasn’t without its critics, specifically because of concerns that promises to the public wouldn’t be delivered. Kimberly Miller from the Municipal Arts Society observed that Jersey City’s recent waterfront rezoning had similarly made promises based on private development that never came to fruition. The legendary Jane Jacobs predicted “with utter confidence” that the 2005 plan “will maybe enrich a few heedless and ignorant developers, but at the cost of an ugly and intractable mistake.” (Like one developer who built 4,000 waterfront condos after contributing heavily to NY2012, the Bloomberg committee behind NYC’s attempt to win the Olympics.)

For the next eight years, the Bloomberg administration moved slowly, in fits and starts, towards acquiring the needed parkland. The 2005 plan had not set aside any funding to buy the park property, a poor strategic move given the steady rise in Williamsburg/Greenpoint property values, which were ironically accelerated by the rezoning. Buying the property from its private owners was complicated to begin with – see this instructive map for the details – and it was clear the city had either misled or been incredibly mistaken about its ability to acquire the parkland.

In 2011 the Parks Department, one of the city’s chronically underfunded agencies, relayed: “The City currently has no funding for the acquisition of this site… and the City has no schedule for the acquisition of this site at this time.” A year later it was more caustic: “We don’t have a bottomless pit of money.”

Today, all the “park” has to offer is a 95-million dollar astroturf soccer field. (The park’s southern neighbor is a half-pleasant plot of parkland owned by the state. A few blocks north, the city purchased a 2-acre slab of concrete for 30 million that hosts concerts and movies in the summer. In total, the City has spent more than $315 million on this project, and is scheduled this year to complete payments on the 7-acre fuel storage site, which will require ample remediation.

That’s a lot of money, but Mayor de Blasio has to understand that a real park is a promise the city made to North Brooklyn, and that as mayor, he has inherited those obligations from Michael Bloomberg, even if those obligations are not legally binding. When de Blasio settled the Central Park Five case as generously as he did, he didn’t owe anything to the five men who had spent years behind bars, but it was the just, appropriate thing for the city to do. In this case, the city needs to make a fair offer to the private owner of the burnt Citi Storage site, who would agree to eminent domain proceedings that might price the property at around $150 million, and then build up the parkland. Mayor de Blasio didn’t create this problem, but he must own up to inheriting it.

Meanwhile, one can only express disappointment at legislators, who are supposed to make sure these promises are kept, or that bad, unenforceable deals are not made in the first place. Watching politicians, from district leaders to members of Congress, thundering away on this issue year after year makes them look impotent, because through their collective efforts they can’t even secure a promised park.

The only forces opposing Bushwick Inlet Park are the budget people in the mayor’s office telling him he can’t afford it. Unfortunately, the city needs to spend this money to defend its land use process. “Land use” is a soporific phrase, but it is so essential to the life of New York City that it is literally first thing many Community Board members and activists learn about local governance. Put (very) simply, zoning changes, like changing the Williamsburg waterfront from industrial to residential, must go through the Community Board, the Borough President, and City Planning Commission, and the City Council. In reality, if the mayor wants something to get done, it usually gets done, and all of these grassroots and institutional political groups claim victory if they can win crumbs like 20% affordable housing, a school, or a park.

Rendering for Greenpoint Landing

In this case, the city is saying they were basically joking about the crumbs, just like they were joking about the 197-A plan the community came up with in 2001. The whole thing was a big charade to let a few wealthy developers make boatloads over the East River view of Manhattan. A year into de Blasio’s administration, this is not how he wants communities to think of the land use process.

The best part is that this would be money well spent. A Bushwick Inlet Park as beautiful as the one promised in glossy 2005 brochures would forever give North Brookynites and their visitors, of all ages, races and incomes, a serene and majestic place to take in maybe the best view in the whole world.

For now, community groups like the Friends of Bushwick Inlet Park and Greenpoint Waterfront Association for Parks and Planning will keep up the fight. Referring to the 300-plus protesters who descended on City Hall on March 12, Councilmember Steve Levin’s spokesman Matt Ojala noted that “Last week’s rally has rekindled the discussion about the City’s promise to deliver.” Every elected official and neighborhood constituency is behind them. And they still might lose.

Mayor de Blasio wants to rezone Jerome Avenue, East New York and Flushing as soon as possible, with more to come. Residents of those neighborhoods should closely watch how events in North Brooklyn unfold, and consider that if the city is going to let developers steamroll Williamsburg/Greenpoint, what gives any other outer-borough community a chance?