A New York City Landmark doesn’t have to be a building. As you’ll discover in this list, landmarks come in all types of shapes and sizes, from the giant Unisphere in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park to the historic cast-iron lamposts of Broadway. We’ve combed through the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designation reports to compile the most unique, non-building New York City landmarks. These don’t include interior landmarks (of which the IRT subway stations are included) or scenic landmarks.

Over the past 50 years, the New York Landmarks Conservancy has helped campaign for landmark designation for hundreds of sites across the five boroughs. Once the LPC does its job of assigning designations, the Conservancy, a separate non-profit organization founded in 1973, continues to offer assistance to the people who care for those New York City landmarks via financial and technical support. On March 7th, join Peg Breen, President of the New York Landmarks Conservancy, for a virtual talk with Untapped New York Insiders to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Conservancy! In this live-streamed talk, Breen will discuss some of the most interesting sites the Conservancy has worked on over the past five decades, including the oldest residence in Manhattan, the site where Frederick Law Olmsted began his landscape design career, and one of the earliest free, African-American settlements in the country.

This virtual talk is free for Untapped New York Insiders. Not an Insider yet? Become a member today to gain access to free in-person and virtual events every week!

1. The Street Grid of Lower Manhattan

One of New York City’s largest landmarks is the street grid of Lower Manhattan, a remnant of Dutch New Amsterdam. The colonial street plan was designated a landmark in 1983. A bronze sculpture of the map can be found at State Street, between the Staten Island Ferry and Whitehall Street. It shows the streets as they appear on the Castello Plan, a 1660 map of Dutch New Amsterdam.

Though they may appear to have different names, streets on the map like Begijn Gracht, Paerel Straet, and Brugh Straet are the same streets we walk today. Now they have anglicized names: Beaver Street, Pearl Street, and Bridge Street. When the British took control in 1664, they changed the names but kept the layout the same. One of the streets even runs through a modern building.

2. A Magnolia Grandiflora Tree

Yep, there is a living tree that is a designated New York City Landmark. The landmarked Magnolia Grandiflora can be found on Lafayette Avenue, between Marcy and Tompkins Avenues, in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. It is one of two trees that have been landmarked by the city. The second tree was a Weeping Beech located next to one of the oldest houses in Queens, the Bowne House. That tree sadly died in 1998 and no longer stands.

Brooklyn’s landmarked tree was planted in 1885 by William Lemken in front of his townhouse. Native to North Carolina, the evergreen blooms with white lemon-scented flowers. It is rare for this type of tree to survive north of Philadelphia. The tree was unanimously designated a landmark on February 3, 1970 due to “its inherent beauty as welI as for its rare hardiness” which made it “a neighborhood symbol and a focus of community pride.”

3. Coney Island Rides

The Parachute Jump, the Wonder Wheel and The Cyclone are all New York City landmarks designated in 1988 and 1989 as symbols of the amusement industry at Coney Island. The Parachute Jump was created for the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. At 262-feet tall, the Parachute Jump was surpassed in height only by the iconic Trylon. After the fair, it was moved to Coney Island where it raised and dropped thrill seekers until 1968.

The colorful Wonder Wheel opened in Coney Island on Memorial Day in 1920 and is now the oldest continuously operating ride at Coney Island. The Cyclone opened in 1927 and is the second-steepest wooden roller coaster in the world. The designation report includes a quote from Charles Lindbergh describing his experience on the coaster: “A ride on Cyclone is a greater thrill than flying an airplane at top speed.”

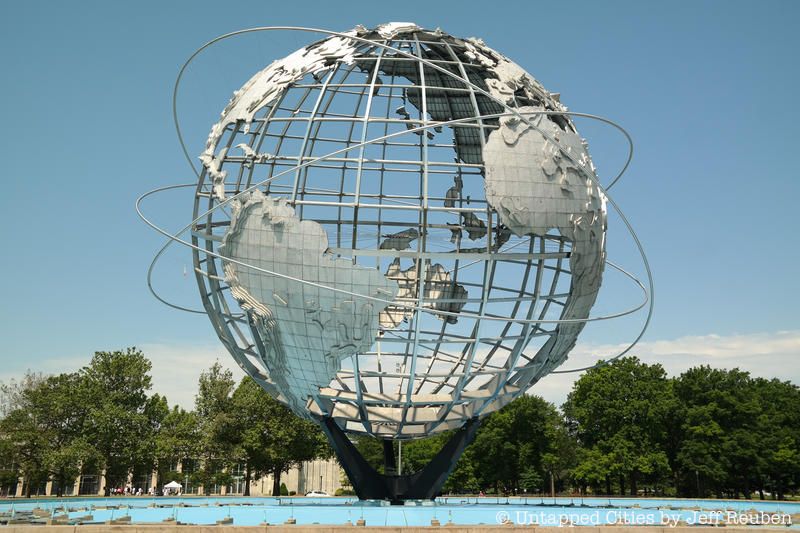

4. The Unisphere

Most structures at World’s Fairs were built to be taken down, but New York City has quite a few remnants of the two World’s Fairs we hosted. One of the most recognizable of those remnants is the Unisphere which stands in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. At 350 tons with a 120-foot diameter, it is the largest representation of Earth on Earth.

The Unisphere was built for the 1964-65 World’s Fair and was designated a landmark in 1995. The other well-known remnant of the 1964 fair is the New York State Pavilion, or what’s left of it. The Philip Johnson-designed structures, which consist of three towers, the “Tent of Tomorrow,” and “Theaterama,” are not landmarked.

5. Lamposts

In 1997 the Landmarks Commission designated sixty-two lampposts and four wall bracket lamps. These fixtures were part of the nearly 100 historic cat iron lamposts known to exist throughout the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens at the time. The earliest lamps were gas-powered and date to the mid-nineteenth century. Electric lamps first appeared on Broadway in 1880. By 1930, the streets of New York were lined with a variety of ornate iron posts.

In the 1950s and 1960s, those decorative fixtures began to disappear. Nineteenth-century lights were largely replaced by modern steel and aluminum substitutes. You can discover where to find 5 of those historic lampposts here!

6. Forest Park Carousel

Not only is the carousel at Forest Park landmarked, but numerous accompanying structures are as well, including the ticket booth, band organ, and of course, the carved wood figures. All of the figures, except for three, were made between 1903 and 1910 by D. C. Muller & Brother, a firm noted for their “expressive anatomical detail and unusual attention to military fittings,” contends the landmark designation report. There are 46 horses, three menagerie animals, and two chariots with benches on the carousel.

This landmark carousel was previously installed in Lakeview, an amusement park in Massachusetts. It was moved to Forest Park, the third largest park in Queens, and opened to the public in 1973. The original carousel which stood in the park in the early 1900s was believed to have been crafted by William Dentzel (son of successful German carousel maker Gustav Dentzel) in 1916. It was destroyed by a fire on December 10, 1966.

7. Sidewalk Clocks

There’s not just one, but seven landmarked sidewalk clocks in New York City. Popular in the late 19th century and often used as advertising, many street clocks have been lost to automobile accidents and sidewalk ordinances. Four of New York City’s landmarked sidewalk clocks are in Manhattan – at 200 Fifth Avenue near the Flatiron Building (in front of the former Toy Center), in front of the Sherry Netherland Hotel at 783 Fifth Avenue, at 1501 Third Avenue, and at 522 Fifth Avenue.

Two of the landmarked clocks are in Queens, one at 16-11 Jamaica Avenue, thought to have been installed by Busch’s Jewelers, and a Wagners Jewelers Clock at 30-78 Steinway Street. There is also one in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, the Bomelsteins Jewelers clock at 753 Manhattan Avenue. All of the clocks were designated in August 1981.

8. Renwick Ruin

Even if a structure is already in ruins, it still might be worth protecting from future decay. While there are many landmark ruins across the globe, there is only one in New York City. That rare distinction goes to the Smallpox Hospital on Roosevelt Island known as the Renwick Ruin. The hospital was designed by noted architect James Renwick Jr. (who designed St. Patrick’s Cathedral) and was completed in 1856.

Around 7000 patients were treated for smallpox throughout the 19 years the hospital was open. The hospital closed in 1875 and services were transferred to North Brother Island. Renwick’s building was used as a training facility for nurses until 1950 when it then fell into a period of disrepair. Already in a state of decay by the 1970s, it was designated a landmark in 1976 for its “special character, special historical and aesthetic interest, and value as part of the development, heritage and cultural characteristics of New York City.”

9. The Bowling Green Fence

The Bowling Green fence has seen some drama. This cast-iron structure in the Financial District was erected in 1771 to surround a statue of George III. As revolutionary fervor took hold of New York City in 1776, a group of rebels knocked the statue down and chopped off the ornaments (either crowns or balls) which once topped the fence posts. You can still feel the jagged edges today.

The designation report from July 14, 1970 states that the fence “fared better than the statue.” We tracked down some of the statue’s remnants here. While the first subway line was being constructed between 1914 to 1919 in Lower Manhattan, the fence was moved to Central Park. Electric lanterns were installed in 1938 when the park was rebuilt, but a restoration project started in 1971 returned the park and the fence to their original designs.

10. Outdoor Pools

The Landmarks Commission has designated many recreational sites across New York City, including outdoor pools. Designated pools include those found at Astoria Park in Queens, Tompkinsville Pool in Staten Island, the Crotona Play Center in the Bronx, Highbridge Play Center, Thomas Jefferson Play Center, and Jackie Robinson Play Center in Manhattan, and Sunset Play Center, McCarren Play Center, and Red Hook Play Center, in Brooklyn, among others.

Most of these structures were built in the 1930s with funding from the Works Progress Administration. The large project required the talent of many architects and landscape architects. Architect Aymar Embury II, landscape architects Gilmore D. Clarke and Allyn R. Jennings, and civil engineers W. Earle Andrews and William H. Latham are names that pop up frequently in these designation reports. As a result of the time in which they were built, many of these recreational sites have wonderful Art Deco designs.

11. The African Burial Ground and Other Cemeteries

While conducting site preparation for the construction of 290 Broadway in 1989, an archaeological research excavation discovered an African burial ground. It turned out to be the oldest and largest known excavated burial ground in North America for both free and enslaved Africans, dating to the middle 1630s. The “Negroes Burial Ground,” a 6-acre site that contained around 15,000 intact skeletal remains of Africans who lived and worked in colonial New York, was unearthed from thirty feet below the street level.

This site was designated a New York City Landmark in 1993. It also holds the distinction of National Historic Landmark and National Historic Monument. Other landmarked cemeteries include the New York Marble Cemetery, Trinity Church Graveyard, Old Gravesend Cemetery in Brooklyn, Brinckerhoff Cemetery in Queens, and many others.

12. Dry Dock #1 at Brooklyn Navy Yard

The entirety of the Brooklyn Navy Yard is a National Landmark, but Dry Dock #1 within it is an individual New York City landmark. It was designated in 1975 for being “one of the great feats of American engineering in the first half of the 19th century.” Built between 1840 and 1851, the dry dock is a below-water-level chamber that can be drained to allow boats to be repaired.

Dry Dock #1 was the first permanent dry dock in the New York City area. Though New York City’s shoreline along the East River was once bustling with maritime activity, there are only 3 active dry docks in operation now at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The docks are a popular setting for film shoots, appearing on television shows like Gotham and Jessica Jones. Another unique maritime landmark in New York City is Pier A at The Battery. The designation report from 1977 that it is the last piece of a maritime complex that once included a firehouse, wharf, and other structures and that it is the oldest type of its structure still standing in Manhattan.

13. Rainey Memorial Gates at the Bronx Zoo

There are multiple New York City landmarks throughout the Bronx Zoo, and not all of them are buildings. The Rainey Memorial Gates were designated in 1967. The free-standing bronze gates were designed by famous American sculptor, Paul Manship, the same artist who designed the Prometheus sculpture (and others) at Rockefeller Center. Manship worked on the gates for five years, eventually producing the beautiful design of animal and plant motifs we see today. The Rockefeller Fountain, donated to the Zoological Society in 1903, is another of the Zoo’s non-building New York City landmarks.

Other gates and gatehouses throughout New York City have gained landmarked status. A few of these include the famous Gothic gates of Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn and the gatehouse on Richmond Terrace at Sailors’ Snug Harbor.

14. Viaducts

There are three viaducts that hold New York City landmark status – the Manhattan Valley Viaduct which runs from 122nd to 135th Streets, the Pershing Square Viaduct which runs on Park Avenue from Grand Central Terminal, and the 155th Street Viaduct which runs from St. Nicholas Place to the Macomb’s Dam Bridge (also landmarked). The Manhattan Valley Viaduct was built for the IRT subway line and the Landmarks Preservation Commission reports that it “is the most imposing and visually impressive aboveground engineering structure of the IRT subway system” and an “excellent example of a double-hinged parabolic braced arch structure. Supporting both the tracks and the 125th Street station, the viaduct is a testament to the skill of the engineers and contractors who designed and built New York City’s first subway between 1900 and 1904.”

The metal and iron Pershing Square Viaduct was designed by the architects of Grand Central Terminal, Warren & Wetmore. it was included as part of the central circulation system of the terminal itself and made Park Avenue a complete north-south avenue. The steel 155th Street viaduct, as the designation report notes, “provides a gradual descent toward the bridge from the heights of Harlem to the west.” Work on the viaduct began in 1890 and it was completed three years later.

15. Eastern Parkway and Ocean Parkway

Both the Eastern Parkway and Ocean Parkway are designated roads in New York City. The Eastern Parkway is significant because it is considered the “world’s first parkway.” It is both a New York City landmark and a National Landmark. Designed by Central Park and Prospect Park architects Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux, Eastern Parkway was intended to emulate the boulevards of Europe, like the Champs-Élysées.

Built in conjunction with Grand Army Plaza and Prospect Park, Eastern Parkway fittingly terminates at the grand Soldiers’ and Sailors’ arch, much like the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. Ocean Parkway, which starts in Kensington, Brooklyn, was also designed by Olmstead and Vaux. Running nearly five miles all the way to Brighton Beach, the parkway featured America’s first bike path, installed in 1894. There were also bridle paths for horses. The parkway was designated a New York landmark in 1975, after which it was restored and repaved.

Uncover more fascinating New York City landmarks in our upcoming Untapped New York Insiders talk with New York Landmarks Conservancy Presiden Peg Breen on March 7th!

Next, check out 10 Restaurants Housed Inside New York City Landmarks and 9 Hidden Apartments in Famous NYC Landmarks